ARPAIO: ADDICTED TO CORRUPTION – Joe Arpaio’s History in U.S. Drug Enforcement & Gov’t Drug Trafficking – PART I (1932-1968)

By Francisco Goldman 9/15/11

INTRO TO SERIES

My initial inspiration for digging a little into Arpaio’s past stems from a post on the Conspiracy Theory Research List (CTRL) from May 11, 2002. Not sure how I happened across it, but nevertheless, what it says is definitely possible. In the post, Charles A. Schlund, from Glendale, AZ, says he was privy to files that showed Arpaio’s connection to the CIA, assassinations, drug running, and gangs (I’m guessing the Dirty Dozen Motorcycle Gang). Here’s part of what Charles said:

http://www.mail-archive.com/ctrl@listserv.aol.com/msg91584.html

Joe Arpaio’s file was one of the files in these papers and he was a corrupt DEA agent at the time of these files. In these files Joe Arpaio was responsible for all drug shipments in the Southwestern United States for the CIA. Joe Arpaio was really a CIA agent who was attached to the DEA for the running of drugs and the removing of political witnesses and assassinations. In Joe Arpaio’s file were notes from his superiors that said that Joe Arpaio was totally without conscience or remorse. Joe Arpaio was signing many orders for assassinations in these files. When the gangs that ran the drugs under Joe Arpaio’s protection and direction would supply Joe Arpaio with girls for sex, Joe Arpaio knew that these girls would have to be killed after he left to protect him [from being exposed]. In his file he never considered anyone’s pain or suffering and did his job for the CIA and DEA without any compassion and was one of the most evil people in the files we had. In these files Joe Arpaio would assume a high position in Arizona after he was no longer needed in the DEA and would help in the setting up of the political witnesses and the running of the drugs and the assassinations from his position in Arizona and would still be under the orders and control of the DEA, which was a covert operation of the CIA.

Even though I don’t believe everything Schlund says it would make sense that Arpaio was involved with U.S. drug running, or at least in covering it up, and has a history with the CIA (especially when working overseas and in the U.S. southwest). Also, Arpaio didn’t have the best rapport with the CIA, especially after blowing the cover of numerous CIA agents while in Mexico (which I’ll discuss in Part II). Nevertheless, Charles might have been on to something!

From Arpaio’s biography on his website (http://www.mcso.org/index.php?a=GetModule&mn=sheriff_bio) you’d have no idea what he actually did with his twenty-five years as a drug enforcement officer:

He began his career as a federal narcotics agent, establishing a stellar record in infiltrating drug organizations from Turkey to the Middle East to Mexico, Central, and South America to cities around the U.S. His expertise and success led him to top management positions around the world with the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). He concluded his remarkable 32-year federal career as head of the DEA for Arizona.

But, with a little digging, the whitewash of his past with the Feds doesn’t seem as rosy as he paints it to be. While he constantly talks about how he took down corrupt police and drug enforcement officers, he never talks about the rampant corruption at higher levels of government (including within the FBN/BNDD/DEA). While some drug enforcement employees, such as Celerino Castillo and Michael Levine, have spoken out against U.S. Government/DEA/CIA drug related corruption and trafficking, Arpaio has remained silent and continues to push his, Harry Anslinger’s, and Nixon’s “get tough” stance on drug users and selected traffickers.

It’s important to note that Arpaio worked for the very bureaucracy that is now supposedly investigating him – The Department of Justice (DOJ). The DOJ is extremely corrupt (i.e. INSLAW & PROMIS) and will most likely not open a can of worms by going after one of its past employees. After all, the DOJ has a long history of covering up cases involved in national security secrets, which Arpaio has plenty of.

Some of the information written in this series isn’t strictly about Arpaio, but has a lot to do with him. For example, Nixon taking control of drug enforcement in 1969 has everything to do with why Arpaio was at the Mexican border for Operation Intercept and arrested Auguste Ricord in Paraguay in 1972. By including the added info about not only Nixon, but also Alberto Sicilia-Falcon, Miguel Nazar Haro, and other CIA and mob figures, I hope it paints a clearer picture of the level of corruption that enveloped Arpaio. U.S. drug running and corruption discussed in this series is only the tip of the iceberg, and Arpaio knows all about it.

In the following four parts I’m going to look a little deeper into Arpaio and the U.S. Government’s corrupt past in the drug trade and enforcement. I hope to show that Arpaio was used as an enforcer of corrupt U.S. Government policies targeting drug users and selected traffickers in order to look tough on crime, while the U.S. Government either trafficked or helped traffic the very drugs they were busting people for using. The CIA then used the funds for off-the-books black-op C.I.A. programs like Operation Condor, which helped fascist Central & South American dictatorships and death squads target union, human rights, and radical movements. On top of his role as an enforcer of corrupt policies, Arpaio, over the decades (’57-present), has helped cover up the Government’s and his role in all of this.

What I’ve dug up is mostly public information and wasn’t hard to find. The dates I’m using, for where and when Arpaio worked, comes from his own resume submitted to the Senate Caucus on International Narcotics Control in 1989. I wonder what more is out there and if it would paint an even clearer picture of Arpaio’s past misdeeds and intentions. Some FOIA requests might turn up some pretty interesting things. Also, I’m sure there are plenty of people out there who have dirt on the bastard. If you have any evidence or anything to contribute to this series please message me at fuckthedrugwar@riseup.net. This series will be updated as new info comes in.

PART I – Early Life, D.C., Vegas, Chicago, Turkey, and Texas (‘32-‘68)

INTRO TO PART I

Part one of this series takes a look at Arpaio’s past, from his birth until his time in San Antonio, Texas as the Special Agent in Charge (SAC) for the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (BNDD). It examines his role as an abusive cop in D.C. and Vegas, and follows his career as a narcotics agent in Chicago, Turkey, and Texas. While researching I couldn’t help but think of how much Arpaio is molded after Harry J. Anslinger (the Federal Bureau of Narcotics director from 1930-1962). Arpaio, to this day, continues to help maintain Anslinger’s regarding U.S. involvement in drug trafficking by enforcing anti-drug user laws, mainly targeting people of color and poor, and not speaking out about the true nature of the drug trade.

HARRY ANSLINGER & THE FEDERAL BUREAU OF NARCOTICS

On June 30, 1930 the Bureau of Narcotics was formed from the remnants of the Narcotics Division and the Treasury Department’s Foreign Control Board. As part of the reorganization, U.S. President Herbert C. Hoover, on the recommendation of Representative Stephen G. Porter (R-PA) and William Randolph Hearst, appointed Harry Jacob Anslinger as acting Commissioner (SOTW 15). The year before, Anslinger had been appointed the assistant Commissioner of Prohibition where he directed the Old Prohibition’s Unit elite Flying Squad, composed of the Treasury Department’s top agents, which worked against interstate and international drug and alcohol smuggling rings. However, it was his marriage to U.S. Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon’s niece, Martha Denniston Leet, that secured the highly sought-after job as Commissioner of Narcotics. The marriage helped him garner the support of the industries, business associations, and social organizations that were investing in drug law enforcement. Among Anslinger’s supporters were the blue chip drug manufacturing and pharmaceutical lobbies, several conservative newspaper publishers, the law enforcement community, the Southern-based evangelical movement, and the powerful China Lobby. Anslinger’s in-law connection with the Mellon family also reinforced his ideological association with other Roosevelt Republican scions of America’s Establishment, that “exclusive group of powerful people who rule a government or society by means of private agreements and decisions.” (SOTW 16). Right off the bat, Anslinger was put to good use by squashing an extortion scheme aimed at implicating President Herbert Hoover and Andrew Mellon in a bootlegging conspiracy worth millions of dollars (SOTW 22).

EARLY LIFE (‘32-‘54)

http://www.freerepublic.com/focus/fr/639754/posts

Joseph Michael Arpaio was born June 14, 1932, the son of a grocer who had immigrated to America from a small town near Naples. Arpaio’s mother died in childbirth, a fact that would affect him profoundly in childhood and provide the basis for one of the only positions he has been willing to articulate thus far in his theoretical bid for governor. “She gave her life for me,” he said. “That is why I’m pro-life.” Arpaio’s father was unable to raise the boy by himself. He enlisted the help of other Italian families in the Six Corners neighborhood of Springfield. Arpaio’s father never laid a hand on him, but his surrogate parents did not hesitate to use the strap. “There was a lot of discipline,” he said. “A lot of discipline. I don’t remember what I did to get whacked. I can’t actually tell you why.” He will not name the family today but said that the punishments did not amount to child abuse. “In those days, you got strapped if you did something wrong,” he said. Arpaio was a poor student, by his own admission, “studying all night to get a C.” At twelve, his father remarried and Joe returned to his house, where it overlooked the town cemetery (Joe’s Law 131). He played team sports all through school, didn’t date, and worked long hours making grocery deliveries up narrow flights of stairs for $3 a day. Tina Mutti, who knew him in high school, remembers him as “a nice kid, quiet and shy,” who was still profoundly affected by the death of his mother. He was often busy working in his father’s store when others were out having fun. “I remember him as a kid being withdrawn,” said Mutti, now 69 and still living in Springfield. “His life was clouded by the fact that he didn’t have a mother’s love. But he certainly came out of it and conquered his demons. I couldn’t believe it when I read what he had done with his life. He was shy.”

When Arpaio graduated from high school in 1951, he left town and never looked back. He joined the Army and was sent to a medical detachment in France, where he got the first law enforcement task of his life: helping French police check prostitutes for venereal disease. He also suffered heartbreak while overseas. A girl he’d met near his basic training at Fort Dix, N.J., mailed back their engagement ring to him.

COP: WASHINGTON D.C. (March ’54 – June ’57)

Since Arpaio had been a boy he longed to join the FBI and be “a real G-man” (Joe’s Law 132). After Arpaio’s discharge from the Army, he took every civil service exam the federal government offered, including tests for the Border Patrol and the Metropolitan Police Department in D.C. He eventually landed the job with D.C. and was placed on a beat in the northern part of town, near Walter Reed Hospital, close to the Montgomery County, Maryland border. He said it was a nice neighborhood, but wasn’t so good for “an aggressive, twenty-one-year-old police man looking to root out and arrest bad guys” (Joe’s Law 132). After six months he asked for a transfer to a tougher beat and was placed in a “poor, black neighborhood” near Fourteenth and U streets. It was there that Arpaio developed his love affair with police brutality. Arpaio says, with pride, that he didn’t win the title of Most Assaulted Cop in D.C. in 1957 – with eighteen serious encounters – for nothing. He walked his beat with a nightstick and blackjack and used both “without hesitation and whenever necessary” (Joe’s Law 134). He describes a blackjack as “a small, leather-wrapped lead weight attached to a strap, allowing the [ab]user to carry it concealed and swing it with maximum force.” He goes on to say that “it can be a devastating weapon, effective in crushing bone and tissue.”

Since Arpaio had been a boy he longed to join the FBI and be “a real G-man” (Joe’s Law 132). After Arpaio’s discharge from the Army, he took every civil service exam the federal government offered, including tests for the Border Patrol and the Metropolitan Police Department in D.C. He eventually landed the job with D.C. and was placed on a beat in the northern part of town, near Walter Reed Hospital, close to the Montgomery County, Maryland border. He said it was a nice neighborhood, but wasn’t so good for “an aggressive, twenty-one-year-old police man looking to root out and arrest bad guys” (Joe’s Law 132). After six months he asked for a transfer to a tougher beat and was placed in a “poor, black neighborhood” near Fourteenth and U streets. It was there that Arpaio developed his love affair with police brutality. Arpaio says, with pride, that he didn’t win the title of Most Assaulted Cop in D.C. in 1957 – with eighteen serious encounters – for nothing. He walked his beat with a nightstick and blackjack and used both “without hesitation and whenever necessary” (Joe’s Law 134). He describes a blackjack as “a small, leather-wrapped lead weight attached to a strap, allowing the [ab]user to carry it concealed and swing it with maximum force.” He goes on to say that “it can be a devastating weapon, effective in crushing bone and tissue.”

It seems as though Arpaio had an affinity for beating people up. One such occurrence he describes in his book involves an individual Arpaio says was “boorishly drunk.” Public intoxication was a crime, so Arpaio and a police trainee approached the man, who was also with his brother. The brother got mad at the police harassment and decided to get involved. “One thing led to another, and soon both men were exhibiting what is technically called ‘disorderly conduct’, culminating when one of the brothers jumped me,” states Arpaio. A crowd of spectators, numbering “over a hundred,” soon gathered around the fight and “one voice in the group made his feelings known, yelling, Kill the cop, kill the cop!” Apparently, no one reacted to his chant. Arpaio and “the trainee beat down the drunks, and then, bleeding and hurt, rushed in and cuffed the bastard trying to incite a riot” (Joe’s Law 135). After describing the incident in the book Arpaio defends his actions by saying, “Never back down, that was my motto. You back down, just once, whether facing two inebriated idiots or a gang of a hundred or more citizens, and you’re finished. You’re finished because nobody will respect you, nobody will count on you, and nobody, not to be too subtle about it, nobody will fear you” (135).

THE DANIEL HEARINGS (’55) & NARCOTIC CONTROL ACT (’56)

In 1955 Congress was challenged to re-evaluate its position on policies towards drug users. Picking up the gauntlet was Senator Price Daniel (D-TX), a member of the Internal Security Subcommittee and a participant in Senate Hearings held in 1955 on Communist China’s involvement in narcotics trafficking. At those hearings, Harry Anslinger (head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics/FBN) convinced Senator Daniel that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was responsible for drug addiction throughout the world, and Daniel deduced that by linking drugs to communism, he could justify a punitive approach toward drug addiction in America (SOTW 152). Out of all this came the Narcotic Control Act of 1956, signed by President Eisenhower on July 18, 1956. In one package, rushed through Congress with virtually no questions or dissent, this Act brought into the law exaggerated new presumptions as to possession of marijuana; increased the minimum and maximum penalties for all drug offenses to two-to-ten years, five-to-twenty years, and ten-to-forty years for succeeding convictions (http://www.druglibrary.org/special/king/dhu/dhu16.htm). The Act was the most important piece of legislation in the FBN’s history. By providing for [higher] mandatory sentencing, it enabled the FBN to more easily acquire informers and thus achieve greater success in the burgeoning war on drugs. However, under the new laws, a teenager caught with a joint was treated as severely as a Mafia don, so many judges resisted the Act, as did many of Anslinger’s critics (SOTW 153). Most politicians went along with Anslinger’s propaganda, and implemented his hard-line approach, thinking it was the best way to curb drug addiction (SOTW 153).

Even though Arpaio wasn’t in the FBN at the time this piece of legislation passed, he certainly benefited from its repercussions. The Act allowed Arpaio, throughout his career, to take advantage of his informers and would allow him to “nickel and dime” sellers and users – in accordance with Anslinger’s policies. Being able to lock up large number of sellers and users, due to the Act, was likely the reason why he was given the huge responsibility of the Instanbul, Turkey office in 1961 after just four years with the FBN in Chicago.

http://www.amacombooks.org/book.cfm?isbn=9780814401996&TextID=1004967

Arpaio’s career took a turn in January 1957, courtesy of Eisenhower’s second presidential inauguration. Standing out among his fellow officers as a veteran, thanks to wearing an American Legion hat, Joe was asked to carry the flag and lead the grand inaugural parade. His unexpected starring role was noted by a sheriff from Nevada who asked him to come to Vegas. Arpaio says that his reason for leaving D.C. was that he “wanted to be a detective, but the promotion rolls were backed up, which meant it could take a while…not to mention I was constantly aching somewhere on my body, from one encounter or another, which made a change of venue sound like a not-so-bad idea” (Joe’s Law 136). Since he was a warrant officer in the Army Reserve, he was able to hitch a ride for free on a military plane heading west, the first plane ride of his life.

LAS VEGAS (June ’57 – November ’57)

Arpaio only lasted six months in Las Vegas as a police officer; however, I’m sure his time in Vegas exposed him to a high level of corruption. The mob had a firm grip on Vegas by the time Joe made it to Sin City. They owned the town and most likely paid off or kept in check the higher-ups at the police department, possibly including Arpaio (whether he knew it or not). It’s also important to note that Vegas was still in the midst of segregation, so Arpaio definitely enforced the color line [just like he did in D.C]. In Joe’s Law, Arpaio states that Vegas was a “relatively small town, and the Vegas PD was similarly small, with only two squad cars out on patrol at any one time” (136). He describes Vegas as “a magnet for reprobates and felons on the run from every state, seeking to grab some money and hide out.” He “nabbed one of those losers literally almost every day.” The only Las Vegas story in his book is about how he stopped Elvis Presley for speeding one day. Stephen Lemons, from the Phoenix New Times, tells it best:

http://blogs.phoenixnewtimes.com/bastard/2010/05/joe_arpaio_arrested_elvis_pres.php

There’s one big fish tale told ad nauseam by Arpaio of how he pulled over Elvis Presley in 1957 when Joe was a rookie cop with the Las Vegas Police Department. Supposedly, Joe stops Elvis for speeding on his motorcycle, a beautiful blonde hanging on to the King from behind. “Maybe because I was young (as was Presley), I let him talk me out of giving him a ticket,” Joe related. Presley then supposedly follows Joe into the station house where he signs autographs for Joe’s fellow officers. Elvis even asks the cops if their garage can tune up his bike.

A couple months before Arpaio came to town, The Chicago Outfit [HC2] and others opened the Tropicana Hotel on Vegas’ Sunset Strip on April 13, 1957. Johnny Roselli helped broker the $150 million partnership for The Outfit, which consisted of Frank Costello (NY), Meyer Lansky (Miami), Carlos Marcello (New Orleans), “Dandy” Phil Kastel (New Orleans), and Morton Downey (best friend & business partner of Joseph Kennedy – JFK & RFK’s dad) (The Outfit 314). Roselli would eventually work with the C.I.A. several years later on their assassination attempts of Fidel Castro.

One day in late ’57 Arpaio’s old partner from D.C., who had taken a job with the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN) in Chicago, phoned him to let him know about a bureau opening. Arpaio saw it as an opportunity to fulfill his dream of becoming a federal agent and jumped at the chance. Through his work as a cop in D.C. Arpaio knew the FBN agent-in-charge in Washington, who was close to the commissioner, who sent him over to the deputy commissioner to be interviewed. During the interview Arpaio was asked if he minded “busting Italians, undercover?” (Joe’s Law 138). After responding, “No, I can do that,” Joe was offered the job.

NARCOTICS AGENT: CHICAGO (Nov. ’57 – Oct. ’61)

With only a budget of $6 million and 250 agents the FBN didn’t have many resources to support Arpaio and the few agents in Chicago (Joe’s Law 138). With no training, Arpaio was asked to hit the Italian neighborhoods and penetrate the mob. On most of his busts he used informants, thanks to the 1956 Narcotic Control Act, to do most of his work. In Joe’s Law Arpaio describes the use of informants: “You can let the informant initiate the contact with the bad guy, then let him make the introductions, then let him negotiate on your behalf, and then, if it makes sense, complete the transaction. Or you can step in at any point in the game and take over the deal.” It was in the Chicago office that he acquired the nickname “Nickel Bag Joe” for his zeal at busting even the most low-level drug salesmen. Arpaio worked the users up the ladder to the pushers. He says that his nickname refers to his ability “to start with a measly five-dollar bag of heroin deal and build on it and follow the trail higher up the food chain” (140). The FBN director, Harry Anslinger, pushed for these types of busts because they brought in the numbers needed for reports, and targeted users, not those with government connections higher up the food chain. The high number of busts Arpaio made while in Chicago most likely led to his promotion overseas.

One interesting bust described in Joe’s Law deals with a Chicago police officer caught dealing heroin. Arpaio got wind of what was going on and arranged a meeting. The officer asked the undercover Arpaio to call him at the police station and sold heroin to him on three occasions in his own squad car. Arpaio said the officer was “shameless, but not stupid – he would flip the switch on his lights and sirens and speed through the city streets while we exchanged money for drugs, effectively prohibiting any surveillance” (143). On the last buy with the cop, Arpaio arranged for the Chicago PD to radio the officer and order him back to police headquarters. Arpaio was sitting in the car when he got the call and drove back to the station, where he was arrested as soon as he got out of the vehicle.

On the night of February 20, 1960 his son, Rocco, was born, but Arpaio wasn’t at the hospital. He was in the Cook County Jail, posing as a drug dealer to get information on a hidden stash of heroin. Apparently, the dealer he was trying to bust took a down payment from Arpaio later to arrive with the dope. Four hours later Joe saw the guy sauntering down the avenue, when all of a sudden a Chicago cop intervened and arrested the guy, who was already wanted. When arrested he didn’t have the heroin on him because he had stashed it in a trash can, which would have been revealed to Arpaio after receiving the rest of the money. Once the arrestee was handed off to other officers Arpaio got the arresting officer to also place him under arrest so he could ask the guy where the dope was while in jail. He eventually found out, but also found out that he missed the birth of his son (Joe’s Law 147).

****************

In January 1959 Fidel Castro and the July 26 Movement took over Havana after a two year fight against the U.S.-backed Fulgencio Batista regime. Cuba had been a hot spot for the U.S. Mafia and they relied on having control in order to use the country to ship heroin to the U.S. Naturally, U.S. companies (including United Fruit), politicians (including Richard Nixon), and the mob (including Santo Trafficante Jr. and Meyer Lansky), who all had investments on the island, fought back against the Movement. Just like in Southeast Asia with the KMT, the C.I.A. looked the other way as anti-Castro Cubans, who they trained, trafficked drugs to help in their crusade against Castro. As we’ll see in Part II, Arpaio and the Miami based anti-Castro Cubans would soon be rubbing the same political shoulders in Mexico.

OPERATION MONGOOSE

Soon after the disastrous Bay of Pigs fiasco, in April 1961, the Kennedy brothers plotted their own attack on Fidel Castro and Cuba and chose General Edward Lansdale and Richard Goodwin, a presidential aide, to come up with the plan – Operation Mongoose. The man the Agency (CIA) selected to run its portion of the Cuban program – its Task Force W – was Bill Harvey (Deadly Secrets 72). In early ’62 Harvey chose 34 year-old Theodore Shackley to oversee the CIA station in Miami, called JM/WAVE (Blond Ghost 73). It included Lansdale’s Mongoose unit, and some 400 CIA case officers. Already the preferred habitat of America’s mobsters, Miami was soon packed with dozens of CIA front companies, thousands of CIA informers and assets, and several drug smuggling terror teams financed by wacky privateers like William Pawley (http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/JFKpawley.htm) (SOTW 260).

SOTW 305

Ever ready to try any innovation in unconventional warfare, the CIA in December 1962 enlarged its mercenary army by trading embargoed drugs for anti-Castro Cubans captured at the Bay of Pigs. Some members of the brigade were sent to secret training camps in Florida and Louisiana to plot murder and mayhem against Castro; others were sent to fight Congolese rebels; and yet others to stamp out Cuban-inspired “brush fire” revolutions in Latin America. Wherever they landed, especially in Mexico, these CIA-trained Cuban Contras turned to drug smuggling to finance their operations, and their syndicate would soon join its Kuomintang, French, Italian, and American counterparts as one of the premier drug trafficking operations. Manuel Artime is a perfect example of the CIA’s lackadaisical attitude toward the drug smuggling activities of anti-Castro Cubans. After his release from prison in December 1962, Artime’s case officer, E. Howard Hunt, placed him in a leadership role in the terrorist Cuban Revolutionary Council (CRC) in Miami. Hunt certainly knew that Artime was using drug money to finance his operations in Miami, as did Hunt’s bosses, James Angleton, Richard Helms, and Tracy Barnes. As the CIA’s domestic operations chief, Barnes was especially well placed to protect Cuban drug distributors. He was in charge of domestic operations involving anti-Castro Cubans and the Mafia, he controlled sixty-four branch offices across America, and, in conjunction with Angelton’s counterintelligence staff, he worked with police forces to provide security for CIA safehouses across America, including any in Dallas, Texas (site of a famous assassination).

*********************

In July 1961, Arpaio attended the U.S. Treasury Department Technical Investigative School – most likely in preparation for his time in Turkey (Arpaio’s 1989 resume). Fellow narcotics agent Rick Dunagan, who attended the training school a year or two later, described what he was taught while there: “They taught us how to pick locks, put on wiretaps, and take surreptitious photographs” (SOTW 298). Although Arpaio’s training was four years late it gave him some tools to take on heavy traffickers in Turkey and the Middle East.

TURKEY (Oct ’61 – Oct ’64)

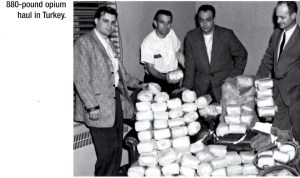

Fourteen years after the Truman Doctrine provided aid to Turkey to ward off communist influence, two years after the Instanbul office first opened, and nine months after John F. Kennedy took office, twenty-nine year-old Joseph M. Arpaio became a Special Agent in Charge (SAC). He was one of six bureau agents sent to work outside of the U.S at the time (Joe’s Law 153). Joe, fresh off his numerous low-level Chicago drug arrests and setups, finally made the big time – a job overseas working on federal drug enforcement in a country that supplied large amounts of raw opium to labs in Marseille, France. At first, the Bureau told Arpaio they weren’t able to fly out Ava or Rocco (then one year old), but maybe after six months they’d be able to scrape some money together for the flight, if Arpaio survived the job. As the six-month deadline came up, Arpaio informed Washington that Rocco could only fly for free until the age of two, which he turned in mid-Feb. ’62. The bureau was able to get them out there just in time, which ended up saving Arpaio’s life. The same day Ava and Rocco landed, Arpaio was scheduled to fly to Beirut for a big case he was working on in Lebanon. He didn’t want to skip his family’s arrival, so he put off the flight instead going the next day. The plane ended up crashing in the mountains killing all aboard. He flew over the wreckage the next day (Joe’s Law 156).

Like in D.C., Arpaio had a penchant for busting heads. One such case ended with the murder of two Turkish farmers. In his testimony in 1989 to the Senate Caucus on International Narcotics Control, which his good pal Dennis DeConcini (there will be more on the DeConcini/Arpaio connection in Part IV) sat on, Arpaio described how he spent three weeks in a Turkish jail for murder:

One of my weekly gun battles in the mountains of Turkey where I killed two Turks, two dope peddlers, and I was indicted along with four other police officers for murder. I sent a cable through State Department channels and nothing happened. Three weeks later, they finally decided, gee, we had better do something with Joe. Of course, I resolved the matter. My indictment was dismissed, and the other police officers had to stand trial; but they were found not guilty. Let me add that we were in the line of duty.

On page 166 of Joe’s Law, Arpaio describes the incident in a little more detail (although he leaves out that he was in jail for three weeks):

I was up in the mountains with a contingent of Turkish cops, approaching Afyon. It had been a typically rough ride, even with my army colonel’s jeep. It was around 10 p.m., and the deal was about to go down. Seven Turks approached, as per arrangement, and delivered 224 kilos of opium via horse and wagon. I had my borrowed jeep and a truck. As per usual, the national policemen were concealed inside the truck. I gave the signal, and the policemen came tumbling out. The seven Turks chose to neither surrender nor flee. They pulled their weapons, a gun battle erupted, and two of the Turkish dealers were killed. The Turkish governor of the region had not been properly forewarned and advised of my investigation. The governor didn’t like this slight and decided to show us who was the boss. Between the governor’s political betters back in Istanbul and the American ambassador, pressure was applied from both sides. The governor crumbled. I can’t say I lost much sleep over the whole affair. It’s not that I was glad the dealers had been killed. I wasn’t. But it happened, and more often than on that one occasion.

On April 1, 1963 Arpaio hit the big time with a one-ton opium bust (http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=W6wyAAAAIBAJ&sjid=_-kFAAAAIBAJ&pg=1970,180512&dq=arpaio&hl=en). The bust was big news for the Bureau and it had an effect on his personal life. I came across this Arizona Republic article describing the impact the bust had on his relationship with his father:

http://www.freerepublic.com/focus/fr/639754/posts

After he helped arrest four Turkish peasants who were guarding a ton of raw opium in 1963, he was prominently quoted in a news story picked up by hundreds of local papers across America. What was more important, however, is that Arpaio’s father saw it in the local paper in Arpaio’s hometown of Springfield, Mass. It was the first time that Arpaio, then 31, knew that he had done something that made his distant father proud of him. “He used to come home after a hard day’s work and fall asleep in the chair,” said Arpaio, whose mother died giving birth to him. “So I didn’t have a father that would take me out to play ball or those kinds of things. He was always tired. I didn’t have that type of childhood…My father was proud, I know, when I made international news. I could see when I got home that he was proud of that.”

In Joe’s Law Arpaio describes how the bust went down, which the Arizona Republic printed in full. Click on the link to read further http://www.azcentral.com/news/articles/2008/06/05/20080605arpaiobook1-09.html

One of Arpaio’s likely informants, starting in 1963 while in Turkey, was Samil Khoury. Khoury, who was the middle-man between Turkish farmers and French labs, was in a key place to provide information to the U.S., and played a part in the U.S. takeover of French drug trafficking (a process that lasted at least a couple decades – around 1954-1973). Just like in numerous other cases, the FBN and CIA let traffickers—in this case Khoury-go about their business in return for information on other traffickers. But, what’s important in Khoury’s case is that he was apparently working in conjunction with one of the top Mafia bosses in the U.S. – Meyer Lansky.

It seems as though no matter how big or how many busts Arpaio made he still wouldn’t have put a dent in Turkey’s opium production, and the subsequent importation of heroin to the U.S. World desire for heroin by far dominated U.S. attempts to squash it. Alfred McCoy, in The Politics of Heroin, likely tells it like it was: “Responding to rising U.S. demand, Marseille’s laboratories doubled their output in just five years, exporting an estimated 4.8 tons of pure heroin to the U.S. in 1965” – during which time Arpaio was the main agent in Turkey (TPOH 63). Yeah, some of the Corsican mob’s opium came from the Golden Triangle, but at that point Marseille was still heavily dependent upon Turkish opium, which was sold under Arpaio’s nose in record number. Arpaio’s busts hardly did anything to curb U.S. heroin importation – if anything it helped drive profit up for the Mafia and U.S. Government. Ironically, the General Director of the Turkish National Police gave the thirty-two year-old Joe the “Exceptional Service Award” in 1964 (Arpaio’s 1989 resume).

San Antonio, TX (Oct. ’64 – Jan. ’68)

In October, Arpaio was transferred to Texas, just as the drug trade between the U.S. and Mexico was heating up – thanks to the U.S. Government and C.I.A. It was a welcomed move by Arpaio who missed “family, friends, phones, paved roads, pizza, cheeseburgers, and television” (Joe’s Law 171). As Special Agent in Charge (SAC) of the San Antonio office, Joe oversaw jurisdiction from the Texas border with Mexico up to Waco. Arpaio came to Texas just as the Goldwater/Johnson election was coming to a head. LBJ ended up wining the November 3rd election with an overwhelming majority of the vote, and the election did much for the direction of law and drug enforcement. According to Christian Parenti in Lockdown America, Goldwater’s campaign (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sz-WhT1EsN4&playnext=1&list=PLDD3BFFB5393B0F57) was the first to “dredge up crime as a presidential campaign issue” (6). At the time the vast majority of criminal justice policy was local and not the business of American presidents. Parenti goes on to state, “The fear of crime became all-American; law and order were emerging as the new political currency with which to unite white voters of disparate classes” (put page number here).

While in Texas, Arpaio worked closely with the Texas Department of Public Safety, the Bexar County Sheriff’s Department, the San Antonio PD’s narcotics squad, and local law enforcement in towns throughout Texas (Joe’s Law 172). Even though Arpaio was the head agent in San Antonio, he still had to do some undercover work. In his book he describes one such case:

I didn’t have enough agents to work all the cases we had going, so even though I was a supervisor I went back undercover. In that guise, I met a Mexican dealer in San Antonio, purchased a sample of heroin, and arranged to buy a considerably larger amount. Cutting to the chase, I enticed the dealer to personally deliver the heroin in front of the federal building that housed the Bureau of Narcotics. When the dealer showed up, I came downstairs, arrested him, and brought him right up to my office.

In 1966, the Bureau of Drug Abuse Control (BDAC) was formed under the jurisdiction of the Food and Drug Administration, which was itself a component of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW). The new agency was charged with pursuing LSD, barbiturates, mescaline, amphetamines, and peyote-type drugs (Joe’s Law 174). Marijuana, heroin, morphine, and other opium derivatives – classified as hard drugs – were still under the control of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics. The new agency recruited close to three hundred agents, many of whom were corrupt Narcotics Bureau veterans, who were able to jump ship and not face charges stemming from their time in the FBN. The split further led to divisions amongst agencies (mainly Customs and the FBN) involved in drug enforcement.

GEORGE H.W. BUSH

George H.W. Bush won the Nov. 1966 U.S. House of Representatives election to represent the 7th District of Texas, becoming the first Republican to represent Houston. Bush’s rise to power in politics during the time Arpaio was in Texas conjures the question of whether the two first met in the late 60’s. Bush had worked for the CIA as an asset since 1948, when he was tasked with recruiting talent while working with Dresser Industries (Prelude to Terror 13). In 1950, after having moved back to Texas, he formed Zapata Petroleum with several investors. After initial success at drilling in Coke County, Texas, the company moved into the equipment leasing and the pioneering area of offshore oil drilling, with its offshoot company – Zapata-Offshore (Prelude to Terror 15). In 1956, Bush moved to Houston and continued his recruitment work for the CIA, but this time he focused on Latin America. In the late 1950’s he was recruited for the CIA’s anti-Castro campaign. He helped give the Agency cover by allowing the CIA to use Zapata’s oil platforms, in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean, to place Cuban anti-Castro “freedom fighters.” Starting in the 1960-1961 period, Bush’s role with the CIA expanded when he was able to place a CIA agent, Jorge Diaz Serrano, in PEMEX – the Mexican national oil operation.

CONCLUSION

Joe probably had good intentions for becoming a law enforcement officer after the Korean War, but quickly developed a thirst for violence while working the streets of Washington D.C. – where he was given the D.C. police department’s honor of “Most Assaulted Cop” in 1957. His abuse of power doesn’t stop there. It’s as if using violence becomes second nature to him, and nothing is out of bounds. The use of violence, at all levels, continues to this day – almost 54 years later.

In Part II I’ll focus on Arpaio’s time with the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (BNDD) while in D.C. and Mexico, and with the DEA in Central and South America, and Boston. It was right after Boston, in 1978, that Arpaio made the trek to Phoenix, Arizona to become the Special Agent in Charge (this will be the focus of Part III). Some highlights of Part II include Operation Intercept and the first time closure of the U.S./Mexico border by Nixon in 1969, how Arpaio fucked up by revealing the identities of numerous CIA agents to the Mexican government, and his role in the Nixon administration’s quest to squash The French Connection, so the CIA could take over the drug pipeline. Look for it within the next month or two.

Again, if you have any dirt on Arpaio you think should be added to any of these parts please email me at fuckthedrugwar@riseup.net.